"Fire Warning"

Aviating with Evans

by Norvin "Bud" Evans,

USAF flight test pilot of all models of the F-104 A, B, C, D, G, CF, and J models at Edwards AFB, California starting 1956

Chief Test Pilot Category I and II and USAF Flight Test Advisor on Category III

Commander of the Fighter Test Operations Division at Wright-Patterson AFB 1963

Most pilots know what the "Fire Warning" light on the instrument panel signifies when it illuminates! Most Pilot Manuals just say: "EJECT"! Well that's well and good but if all pilots followed those instructions when a Fire Light came "On", the military would be a lot shorter on aircraft than it is. When the light comes "On" it gets your full attention! Fortunately most of us have checked for more definite signs of actual fire before panicking. What I am about to relate to you happened to me in 1960. I had been selected to be the USAF's test pilot on the Northrop N-156F (Later to be designated the F-5A). The aircraft was built on Northrop funds but someone in the USAF decided at the last minute that they should put some money into the project and put money into Northrop's program. (I'm not sure but believe the amount was $33 million). Regardless, it was enough to have the USAF Flight Test Center furnish a test pilot and flight test engineer to work right along with the Northrop test crew.

The arrangement was for me to fly from the very beginning of the testing as though I was a company test pilot. This was something the military never did and it is to Tom Jones (President of Northrop) credit that he went along with the agreement. Lew Nelson was the Chief Test Pilot for the company and was scheduled for the first flight. In order to get his "Bonus" he had to take the aircraft supersonic but the landing gear unsafe light remained "On" so he had to return and land. I was chasing him in an F-100F with a Northrop photographer in the back seat and although we could not see any problem with the landing gear from the outside, the prudent thing to do was to cut the flight short. After the ground crew adjusted the micro-switches on the landing gear, Lew made the second flight. It was supposed to have been my flight but with bonus money on the line for Northrop's pilot, I couldn't argue. From that point on in the program, I rotated flights with Lew and later some other Northrop Test Pilots. I chased all of the Northrop flights and the incident that I am about to relate happened on one of those flights.

One of the big problems with it not being a USAF test aircraft was that the J-85 engines (which it had been designed to use) were available only for the three T-38's that were being used in the USAF funded test program. The N-156F had 2 early J-85 engines that had no afterburners and fewer compressor stages than the T-38's engines. They were deigned for a missile and the total thrust of the two engines was less than one of the T-38's engines in afterburner. Our testing began on the 31st of July, 1959 and we were operating under the handicap of short funding and it was nearly one year after the first flight when the following event took place. It was July 1960 and we were flying in extremely hot weather from a runway that was nearly 3,000 feet above sea level. The good news was that the runway was 15,000 feet long with a 7 mile lakebed overrun.

We reached the stage in our test program where we were to see if the aircraft could fly with a 2,200+ lb bomb under the centerline station. This put the center of gravity right at the design forward limit. The engineers predicted that the airspeed would have to be considerably above normal to have enough elevator power to lift the nose-wheel from the runway. It was Lew's turn to fly the first take-off and my flight would be to drop the bomb. I was flying the chase flight in an F-104D with a Northrop photographer in the back seat. We had to wait until Lew was a couple of thousand feet down the runway before I released the brakes on the F-104. It was Noon on a 105-degree day and having the very heavy weight with low thrust engines we had predicted it would take 8 to 10,000 feet of roll to get the N-156 airborne. I was judging my timing so as to be airborne with my gear up and in a closing position when he lifted off the runway (if the aircraft was really going to fly with that heavy load).

The Starfighter accelerated rapidly and as soon as I was airborne I retracted the gear and left my flaps in the "Take-Off" position. The J-79 engine's afterburner had four segments which allowed the pilot to make power adjustments. But because of the tremendous power of the engine the pilot had to use care in the amount of throttle movements he made while operating through those four segments, to prevent the engine from suffering a compressor stall (which was not a desired situation at low altitude). A "Chase Pilot's" job is to lock his eyes on the aircraft on which he is flying safety chase and cannot take time to check his own instruments This can be serious business if something goes wrong with your aircraft such as having a fire warning light come on, as you will probably not see it until it is too late to do anything about it. Had I not had the Northrop man in the back seat I would probably not be here to write my account of this adventure!

|

I was gaining on the N-156 and we were close to 10,000 feet down the runway when it literally leaped into the air. The photographer called over the hot mike about fire coming from the back of the aircraft. This puzzled me as we were about 50 feet behind the N-156 and about 20 feet above him and I had my eyeballs locked on to it. My first thought was: What's he talking about? I answered that I didn't see any fire coming from the back of Lew's aircraft. His anxious reply peaked my immediate attention! "Not his aircraft. OURS!" We were now about 300 knots and accelerating when I glanced at my left rear view mirror that was mounted on my windscreen frame. I will never forget nor have I ever been able to adequately describe the sight. All I could see was an extremely bright large orange fireball with a shower of orange sparks blazing from the outer portion of the ball of fire. It was a bright desert noon and even so the fireball was almost blinding. It appeared as though the whole aircraft just behind the rear seat was merrily blazing away. If the fire warning light was "ON" I will never know. Instinct made me retard the throttle rapidly being conscious that too quick of a movement from afterburner towards "Idle" would cause me to lose the engine. We were approaching the end of the 15,000 foot runway; the altitude was about 100 feet as I guess I pulled back a little the stick while reducing the power as fast as practical. I needed to slow the aircraft quickly and set it down on the lakebed. Ejecting seemed not to be an option at that low altitude. I had full tip tanks and was afraid that if they didn't jettison evenly, we would roll right into the ground. I vaguely remember the tower calling me advising that my aircraft was on fire. It was a little late as I was already well aware of the fact!

|

Speed brakes were already extended while adjusting my overtake speed of the N-156F.I put the landing gear handle to the "Down" position, although I knew I was still above the gear down speed limit. I also was aware that I had to get the aircraft on the ground immediately. The landing gear lights indicated that they were down and locked. There were many things racing through my mind in those long seconds: First I knew that my best method of getting on the ground was to make a gentle turn so as to help judge my height above the flat steaming lakebed surface which produced a severe "Mirage" effect. As soon as I reached 225 knots I lowered full flaps, rolled wings level and put the aircraft on the ground above 200 knots. I knew that the lakebed had very large holes on the surface, which was not marked by runway lines, but I had no choice. (When it rained every few years the lakebed would flood. In the following weeks the wind would blow the water back and forth over the surface smoothing it to a hard smooth surface. The water also had to find its way down to the underground river that was 1,600 feet below the lake, thus these large holes were created in various parts of the large lake surface).

|

My flight controls had become noticeably stiff and I was thinking that the aft section of the F-104 might be burning off of the rest of the aircraft. Once on the ground I began to realize there was no way of avoiding one of these holes, even if I saw it front of me. The "Mirage effect" made everything in front appear as though there was a lake that I was running into. When I was solidly on the ground I shut down the engine, I pulled the Drag Chute handle. I felt a slight tug on the aircraft and then it felt as though we accelerated as the chute obviously departed from the aircraft. Shutting down the engine caused me to lose my power brakes, nose wheel steering and radio. All that I could do was pray we would miss the lakebed holes (which would have ended this adventure and the two of us permanently). The Starfighter rolled and rolled and rolled. It seemed as though it would never come to a stop. My next sudden concern was a big yellow fuel truck looming directly in front of me. There was a North Base airfield on the Northwest corner of Rogers Dry Lake and the truck was sitting there on the ramp. I pushed on the manual brakes but with very little effect. I can't adequately describe the feeling of helplessness while waiting for the aircraft to gradually slow to a stop. The photographer was out of the back seat on the hot lakebed before we were fully stopped. I wasn't far behind him!

|

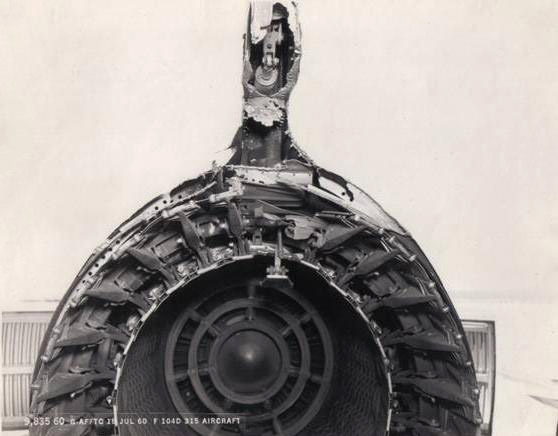

The picture shows the Stabilator actuator which was melted and locked in the landing position it had been placed just before touchdown.

Quickly moving to the rear of the aircraft I expected to see that the aft portion of the fuselage would be severely scorched. It wasn't until I walked behind the tail and looked back at the tailpipe that I could see what had been happening. One of the afterburner nozzle guides support arm had failed allowing the section to drop down directly into the full flow of afterburning fuel and directed it straight up into the horizontal stabilizer. The fire burned through the titanium upper engine housing and then burned the rudder and inside of the vertical stabilizer. This housed the actuators for the rudder and stabilator. Both actuators were melted, as were the hydraulic lines to them. It was unbelievable that the aircraft was controllable until touchdown although it was assumed that the controls were frozen in the landing attitude before we landed. It took 10 minutes for the crash trucks to reach us and by then we were both relaxed and ready for the cold drink of water they handed us. It turned out that the "Fire Warning Harness" did not reach the area where the fire occurred and therefore it was believed that the light never illuminated. You couldn't prove it by me but it wouldn't have changed the way I responded to the situation once I was made aware that we were on FIRE! Yes the Northrop photographer did fly with me again. In fact we flew together on a number of subsequent flights. I was always happy to have him with me.

F-104D serial number: 57-1315

date: July 18, 1960

Copyright by Norvin "Bud" Evans compiled by: Hubert Peitzmeier

update: April 28, 2008![]()